Detection engineering is an important role and task for a security analyst. It involves developing processes that will guide you as an analyst to identify threats, detect them through rules and processes, and fine-tune the process as the landscape changes.

Learning Objectives

- Understand what Detection Engineering is.

- Understand the Detection Engineering Lifecycle.

- Identify various frameworks used in Detection Engineering.

Task 2 What is Detection Engineering?

Detection Engineering

Cybersecurity is growing and evolving at a rapid rate, compounded by the progress made in technology. With this, adversary actions are also evolving, and cyber attacks are becoming so rampant and sophisticated that it is difficult to keep up with them. Additionally, security teams must develop and adapt to new mindsets and practices that will aid them in keeping up with adversaries. That’s where detection engineering comes in.

Detection engineering is the continuous process of building and operating threat intelligence analytics to identify potentially malicious activity or misconfigurations that may affect your environment. It requires a cultural shift with the alignment of all security teams and management to build effective threat-rich defence systems.

Detection Types

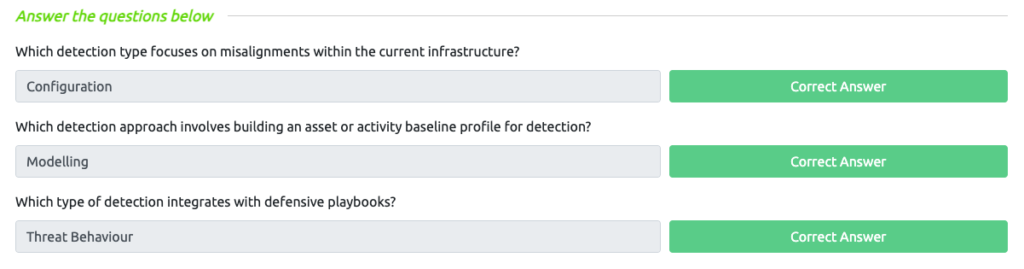

Threat detection can be viewed from two perspectives, each comprising two categories: The first one, Environment-based detection, focuses on looking at changes in an environment based on configurations and baseline activities that have been defined. Within this detection, we have Configuration detection and Modelling.

In the second perspective, Threat-based detection focuses on elements associated with an adversary’s activity, such as tactics, tools and artefacts that would identify their actions. Under this, we have Indicators and Threat Behaviour detections.

Configuration Detection

Under this detection, we use current knowledge of the known environment and infrastructure to identify misalignments. Configurations can cross domains, including network, asset or identity.

Configuration detection has the following benefits and challenges:

| Benefits | Challenges |

|---|---|

| The easiest form of detection to create and maintain in static environments. | Difficult to maintain in dynamic environments. |

| Under perfect conditions and coverage, it detects all malicious activity. | Limited visibility reduces effectiveness. |

| Individuals with different expertise can execute the detection. | There’s an assumption of knowledge of the working infrastructure and configurations for effectiveness. |

| Easy to combine with other detections for forensics and response. | Frequent configuration changes can result in high false positives. |

Modelling

Threat detection under this type is done by defining baseline operations and activities and recording any deviations that occur. The primary assumption of this approach is that malicious activity can be sufficiently identified from benign activity.

The approach involves building an asset or activity profile that includes baseline events, time and data threshold. An in-depth look into baselining shall be discussed in the next task.

Some of the benefits and challenges of this detection method include the following:

| Benefits | Challenges |

|---|---|

| Used to identify unknown adversary activities due to model changes and not threat characteristics. | Provides no context of threat activity during investigations. |

| Easy to maintain in very static environments. | Difficult to maintain in dynamic environments. |

| Limited visibility reduces effectiveness. | |

| Assumes in-depth knowledge of the working infrastructure and configurations. | |

| Potentially adds existing malicious activity into the model. |

Indicator Detection

As a reminder, indicators are pieces of information that identify a state and context of an element or entity. There are both good indicators used to identify legitimate activities or resources, such as those used in whitelists, and bad indicators used for suspicious or malicious resources, such as in blacklists or malware IPs.

IOCs are commonly referenced and derived from investigations against malicious events. By observing threat activities and investigations, analysts can use identified indicators to craft detections and adapt them based on an adversary’s rate of change.

Some of the benefits and challenges of this detection method include the following:

| Benefits | Challenges |

|---|---|

| Fastest detection to create and deploy. | The value of detection depends on the adversary’s rate of change. |

| Indicators raise specific threat contexts. | Retroactive in nature, one needs to observe the indicator first. |

| Useful for enriching data sources and detections. | Limited to some indicators that can be processed at a time. |

| Practical for scoping environments post investigation of indicators. | Unknown indicator expiry or change timelines can lead to false detections. |

Threat Behaviour Detection

Analysts will look at an adversary’s Tactics, Techniques and Procedures (TTPs) to conduct an attack, regardless of any specific indicators. This makes detection more scalable beyond indicators.

Through this detection, analysts can focus their efforts more efficiently on responding to the threat and mitigate against it instead of utilising time and resources to understand how and why alerts were triggered. Additionally, threat behaviour detection can be paired with established workflows and playbooks to provide best practices that can be followed during an investigation.

Some of the benefits and challenges of this detection method include the following:

| Benefits | Challenges |

|---|---|

| Withstands the adversary’s rate of change. | Due to the adversary’s complexities, lots of data is required to provide complete coverage. |

| Easy to tune and adapt to different environments. | Moderately difficult to make initial implementations due to baseline assessments. |

| Low rates of false positives. | Only detects similar threat behaviour based on the set analytic. |

| Integrates with defensive playbooks and automated remediation plans. | Modifications must be made if detections must be reused across industries. |

Combining these forms of detection results in more robust defence systems. For example, model-based detection can be strengthened with expert-led configuration detection to reduce the chances of having false positives throwing alerts.

Detection as Code

Detection as Code (DaC) is a structured approach to writing detections by incorporating software engineering best practice principles. This means that detection engineers and analysts will handle detection processes and logic as code, offering scalability to address the rapidly changing environments and adversary capabilities.

DaC offers a code-driven workflow that creates fine-tuned detection processes that introduce critical elements found in Continuous Integration/Continuous Development (CI/CD) workflows. Some of these elements include:

- Version Control: Most SIEMs and EDR products lack the ability to track changes made to alerts and their definitions. By introducing version control, detection rules and processes can be quickly reviewed, tested and accounted for, enabling higher-quality detections.

- Automation workflows: By adopting a CI/CD workflow, detection testing can be automated and allow quick transition and production delivery.

With that, Detection as Code provides the following benefits:

- Customisable and Flexible Detections: Using a common language for detections, such as Sigma and YARA, offers an opportunity for DaC to be vendor-agnostic and be deployed across numerous SIEM, EDR, and XDR solutions.

- Test-Driven Development: Quality testing of detection code can ensure that blind spots and false positive tests are identified earlier in the process and promote detection efficacy. Additionally, this approach improves the quality of detections and ensures they are well documented.

- Team collaborations: Using the CI/CD workflows eliminates isolation between security teams and fosters collaboration through the coding process.

- Code Reusability: With detection patterns emerging over time, engineers can reuse code to perform similar functions across different detections, ensuring that the detection process moves on faster since there won’t be the need to start from the beginning.

Task 3 Detection Engineering Methodologies

Detection Gap Analysis

The first step involves looking at the environment and identifying key areas where organisations can improve threat detection. This process is also known as threat modelling and can be done in the following ways:

- Reactive: Assessing the most recent internal incident reports, taking note of the lessons learnt from the attacks and curving out missed areas of possible detection.

- Proactive: Using the ATT&CK framework and various threat intelligence sources to map out potential areas of attack and the various TTPs that an adversary against your environment may use.

Note: Threat modelling in this context differs from the detection type discussed in the previous task.

Datasource Identification and Log Collection

With information about the relevant threat actors, TTPs and potential risks the organisation may face, sources of relevant data associated with the risks need to be identified. This will determine what logs are currently available that will aid in defining detections against the threats and know which ones are missing and which are necessary.

Baseline Creation

Before using all the collected information about adversaries, their TTPs and any malicious behaviour, security analysts need to know what normal behaviour is and set their security baselines. This will be a rolling process and requires participation from all departments within an organisation.

Setting up security baselines involves identifying the different types of devices running within an organisation based on their operating system, services and functions. Security baselines can be grouped into two categories:

- High-level: This sets broad OS independent standards guided by a specified security policy.

- Technical: This consists of OS-based configuration standards outlining different system functions and the intended behaviours or activities. For example, technical baselines outline OS hardening policies, network activities, Identity and Access Management (IAM) policies, and application policies.

Log Collection

Once the baselines and sources of internal data have been identified and prioritised, the collection of logs and metadata useful for threat detection should be done. Depending on the infrastructure setup, a centralised system may aggregate all logs using network sensors for network data and services such as Sysmon to collect host data.

Rule Writing

Based on the infrastructure setup and SIEM services, detection rules will need to be written and tested against the data sources. Detection rules test for abnormal patterns against logged events. Network traffic would be assessed via Snort rules, while Yara rules would evaluate file data. Check out the Snort and Yara rooms for more.

As part of the Detection Engineering module, we shall look at Sigma, a generic signature language used to write detection rules against log files.

Deployment, Automation & Tuning

Tested detection rules must be put into production to be assessed in a live environment. Over time, the detections would need to be modified and updated to account for changes in attack vectors, patterns or environment. This improves the quality of detections and encourages viewing detection as an ongoing process.

Task 4 Detection Engineering Frameworks 1

MITRE’s ATT&CK and CAR Frameworks

MITRE is well-known for publishing identified CVEs that adversaries would look to exploit for their malicious activities. Additionally, MITRE provides knowledge-based access that security analysts can use to track tactics and techniques commonly used by malicious actors across different platforms such as Windows, macOS, Linux, and Mobile.

The ATT&CK framework helps map out adversarial actions based on the infrastructure in use for detection engineering. It guides what to look for, especially as part of the detection gap analysis phase.

The CAR (Cyber Analytics Repository) knowledge base is used to detect adversary behaviours and prioritise them based on the ATT&CK framework.

Click to enlarge the image.

Pyramid of Pain

This is a well-known framework in the industry and is mainly used to showcase the pain for the adversary; if the defenders detect their TTPs, then how difficult and/or costly it would be for the adversary to change their TTPs.

Cyber Kill Chain

Thanks to a military concept of an attack strategy, Lockheed Martin formulated the Cyber Kill Chain framework to define the necessary steps followed by adversaries. The framework focuses on seven crucial phases that cyber-attacks commonly follow:

- Reconnaissance

- Weaponisation

- Delivery

- Exploitation

- Installation

- Command & Control

- Actions on Objectives

As a security analyst and detection engineer, understanding the Cyber Kill Chain will give you the knowledge to recognise intrusion attempts crafted by an adversary and map them into your detection plan. The Unified Kill Chain was developed to complement the Cyber Kill Chain by combining it with other frameworks, such as the MITRE ATT&CK framework. This expanded the original kill chain into 18 phases to cover every known element of a cyber attack.

If you are unfamiliar with these frameworks, check out these rooms that will provide an in-depth understanding:

Task 5 Detection Engineering Frameworks 2

Alerting and Detection Strategy Framework

Palantir developed the ADS Framework to provide a guideline for documenting detection content. A significant challenge faced by security teams, and Palantir being no exception, is alert fatigue and apathy, mainly caused by poor means of developing and implementing detection alerts that would result in effective incident response and mitigation. The ADS Framework seeks to address this challenge and provide a guideline for constructing effective detections and alerts.

The ADS Framework has a strict flow that detection engineers must follow before publishing detection rules into production. The stages involved are:

- Goal: Describes the intended reasons for setting up the alert and the type of behaviour that needs to be detected.

- Categorisation: Mapping the detection to the MITRE ATT&CK framework to provide analysts with information on the TTPs for investigation and areas of the kill chain where the ADS will be used.

- Strategy Abstract: Provides a top-level description of how the detection strategy being implemented functions by outlining what the alert will look for, the data sources, enrichment resources and ways of reducing false positives.

- Technical Context: Describes the technical environment of the detection to be used, providing analysts and responders with all the information needed to understand the alert. Security analysts should align this information with the platforms and tools for collecting and processing threat alerts.

- Blind Spots and Assumptions: Describes any issues identified where suspicious activities may not trigger the strategy. Assumptions and blind spots help clarify ways the ADS may fail or be bypassed by an adversary.

- False Positives: Outlines occurrences where alerts may be triggered due to misconfigurations or non-malicious activities within the environment. This makes it easy to configure your SIEM to limit alert generation to only targetted threats when pushed to production.

- Validation: Every detection needs to be verified, and here, you can outline all the steps required to produce a true-positive event that would trigger the detection alert. Consider this a unit test, which can even be a script or scenario used to generate an alert. For an effective validation:

- Develop a plan that will produce a true-positive outcome.

- Document the process of the plan.

- From the testing environment, test and trigger an alert.

- Validate the strategy that triggered the alert.

- Priority: Set up the alerting levels with which the detection strategy may be tagged. This section provides the details of the criteria used to set up the preferences, and it is separate from the alerting levels shown through the SIEM.

- Response: Provides details of how to triage and investigate a detection alert. This information is helpful for analysts and responders to be able to prevent extreme repercussions.

Detection Maturity Level Model

Ryan Stillions brought forward the Detection Maturity Level (DML) model in 2014 as a way for an organisation to assess its maturity levels concerning its ability to ingest and utilise cyber threat intelligence in detecting adversary actions. According to Ryan, there are two guiding principles for this model:

- An organisation’s maturity is not measured by its capabilities of obtaining valuable intelligence but by its ability to apply it to detection and response.

- Without established detection functions, there is no opportunity to carry out response functions.

The DML model comprises nine dedicated maturity levels, numbered from 0 to 8, with the lowest value representing technical aspects of an attack and the highest level representing abstract and intelligence-based aspects of an attack. The individual levels can be described as follows:

- DML-8 Goals: The pinnacle of the model represents organisations that can detect an adversary’s motive and goals. Unfortunately, it is near impossible to conduct detections solely based on goals, as in most cases, it is a guessing game based on behavioural findings from lower DMLs.

- DML-7 Strategy: Following closely after DML-8, this level is non-technical and represents the adversary’s intentions and strategies to fulfil them. Organisations at this level would have a mature intelligence source that will ensure they have context about an adversary’s plans, which will be helpful to responders.

- DML-6 Tactics: Organisations must be able to detect a tactic being used by an adversary without necessarily knowing which technique or tool they used. Tactics are detectable after observing patterns of events that aggregate over time and conditions.

- DML-5 Techniques: Techniques usually are specific to an individual or APT. Therefore, adversaries leave behind evidence of their attack habits and behaviours and organisations that can detect when a particular threat actor is within their environment are at an advantage.

- DML-4 Procedures: Organisations require to detect sequences of events from an adversary at this level. They will be very organised and follow a given pattern, such as the pre-exfiltration reconnaissance.

- DML-3 Tools: Detection of tools can fall into two phases: the

transfer phasewhere the tool is downloaded via the network onto a host device and resides on a file system or in memory. And the second is detecting through the tool’sfunctionality and operation. In some cases, this detection level would require organisations to perform reverse engineering against adversarial tools, making it difficult to cause havoc by understanding their tools’ capabilities. - DML-2 Host & Network Artefacts: Most organisational resources would be spent gathering IOCs and artefacts as threat intel at this level. Unfortunately, in most cases, indicators are observed after the fact. The threat actor would likely be causing havoc within the network when artefacts are picked up and investigated. This has been described as “chasing the vapour trail of an aircraft”.

- DML-1 Atomic Indicators: This level comprises organisations utilising threat intel feeds in the form of lists of IP addresses and domains to detect threats.

- DML-0 None: At the bottom of the model, organisations that operate at this level have no detection processes established.

In the original publication of the DML model, Ryan described four critical use cases for the model, namely:

- To provide a lexicon for more accessible communication of threat information.

- To assess detection maturity against monitored threat actors.

- To assess the maturity of security vendors and products in use.

- To provide context to analysts by including the DML levels in Yara rules, Snort signatures and SIEM correlation rules.

View Site

Scenario: THM is seeking to establish a detection engineering process to detect changes made to privileged and administrative groups and accounts in their Active Directory. As a detection analyst, you have been tasked with developing the strategy based on a set of questions. Each question comes with one correct answer; therefore, it is up to you to identify and select it. You will have three attempts to complete the exercise before it resets.

Use the Unusual Powershell Host Process ADS Framework template below as a guide to what each stage of the framework requires.

| ADS Stage | Description |

|---|---|

| Goal | Detect when PowerShell is loaded into an unusual host process. |

| Categorisation | Execution/Powershell |

| Strategy Abstract | Monitor module loads via endpoint tools.Assess the process that loads PowerShell DLL.Alert on unusual PowerShell host processes. |

| Technical Context | Powershell, built on the .NET framework, is a command-line shell and scripting language for performing system management and automation. It is a DLL entitled system.management.automation.dll but also may exist as a native image or through the process powershell.exe.Attackers leverage Powershell as it provides a high-level interface to interact with the OS without requiring the development of functionality in C, C# or .NET. Sophisticated adversaries may opt for the OPSEC-friendly method of injecting Powershell into non-native hosts, commonly identified as unmanaged PowerShell. |

| Blind Spots & Assumptions | Endpoint tools are running correctly.Endpoint logs are reported and forwarded to the SIEM.SIEM is indexing endpoint logs successfully. |

| False Positives | A legitimate Powershell host is used and not suppressed via a whitelist. |

| Priority | Medium |

| Validation | Perform the executions:Copy-Item C:\Windows\System32\WindowsPowerShell\v1.0\powershell.exe -Destination C:\windows\temp\unusual-powershell-host-process-test.exe -Force Start-Process C:\windows\temp\unusual-powershell-host-process-test.exe -ArgumentList '-NoProfile','-NonInteractive','-Windowstyle Hidden','-Command {Get-Date}' Remove-Item 'C:\windows\temp\unusual-powershell-host-process-test.exe' -Force -ErrorAction SilentlyContinue |

| Response | Compare suspect PowerShell host against whitelist entries.Check the digital signature of the binary.Identify the execution behaviour of the binary. |

Adopted from the ADS Framework Examples.

To start, click View Site.

Happy Hunting!

Leave a Reply